|

RICHARD PHILLIPS FEYNMAN

welcome feynman - PAGINE 1 2

ODE TO A FLOWER - look how beautiful it is

There is no harm in doubt and skepticism for it is through these that new discoveries are made ...

Come possono diventare parte del

quotidiano della gente comune le scoperte della fisica quantistica?

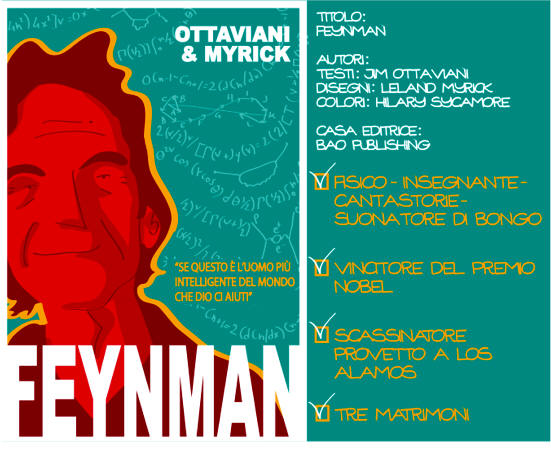

* FEYNAMN A FUMETTI accurata bibliografia pubblicatA dalla casa editrice BAO Publishing “Feynman” racconta la scienza in modo diverso dal solito - divertente e stuzzicante ricca di aneddoti ma anche di spiegazioni scientifiche ... Come la scena in cui Feynman al CERN chiede di quale esperimento si tratti ... ' è la sua teoria della rinormalizzazione della carica Dottor Feynman ! Se riesce l’esperimento dimostrerà la sua validità '

E – chiede Feynman – quanto è

costata questa roba ? -

' Trentasette milioni di dollari

'

tra i best seller del

New York Times Feynman ci racconta in prima persona la sua

carriera gli studi

gli amori la passione per la bella

vita la partecipazione al Progetto Manhattan e le sue

teorie. Un libro chiaro

appassionante illuminante

che vi farà provare dispiacere per non aver potuto conoscere di

persona l'uomo eccezionale che era .

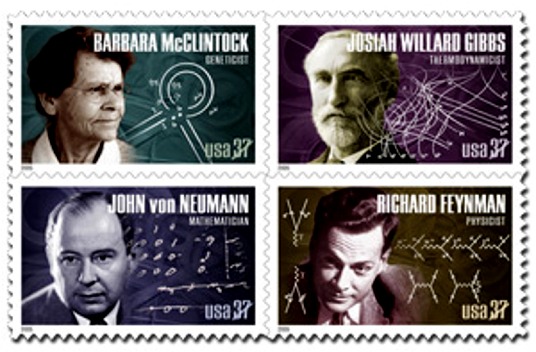

Celebrating more than a century of science on U.S. postage stamps 2005 usps.com

* Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts la scienza è la fede nell'ignoranza degli esperti E' necessario insegnare ad accettare e insieme rifiutare il passato, esercitando un gioco di equilibrio che richiede molta abilità Di tutte le discipline la scienza è l'unica che racchiude in se stessa il monito sul pericolo costituito dalla fede nell'infallibilità dei più grandi maestri della generazione precedente globalist.it *

La stessa emozione la stessa meraviglia e lo stesso mistero nascono continuamente ogni volta che guardiamo a un problema in modo sufficientemente profondo. A una maggiore conoscenza si accompagna un più insondabile e meraviglioso mistero che spinge a penetrare ancora di più in profondità the value of science

Who was

Richard Feynman? As a child, not so impressive--he didn't speak a word until he

was three. But he mastered differential calculus when he was 15, earned a

bachelor's degree from MIT and then a doctorate from Princeton ...

We are at the very beginning of time for the human race It is not unreasonable that we grapple with problems But there are tens of thousands of years in the future Our responsibility is to do what we can - learn what we can improve the solutions and pass them on - rf

L'integrale feynmaniana

comprende circa 50 volumi di opere autografe o trascritte

da amanuensi fedeli, di biografie, agiografie, esegesi e narrazioni infedeli;

decine di audiocassette con registrazioni di lezioni, conferenze e qualche a

solo ai bonghi; album di immagini del protagonista, dal ragazzino in calzoncini

corti, al sessantenne in forma e calzoncini dell'identica foggia mentre parla di

nanoscienze. Fino a l'ultima, del 1986, durante una conferenza stampa a

Washington. Quasi settantenne, ha davanti a sé ha un bicchiere di ghiaccioli con

dentro un pezzo di gomma, sta per mostrare ai giornalisti come mai la navetta

spaziale Challenger si sia disintegrata pochi secondi dopo il lancio, il 28

gennaio.

.

THE

PLEASURE OF FINDING THINGS OUT . NON MI PIACCIONO GLI ONORI

Yes ! Physics has given up. We do not know how to predict what would happen in a given circumstance and we believe now that … the only thing that

can be predicted is the probability of different events.

C'è moltissimo spazio in basso Nel 1959 Richard Feynman, padre della bomba atomica e della fisica quantistica, introduce i concetti alla base delle nanotecnologie nel corso di una lezione universitaria che passerà alla storia con il titolo di “There's plenty of room at the bottom”. C'è moltissimo spazio in basso, per l'appunto. Il basso cui si riferisce il fisico statunitense è quello delle dimensioni submolecolari, dove il vuoto esistente tra i vari atomi di materia garantisce sufficienti “margini di manovra” per realizzare qualunque cosa.

Sessanta e più anni fa, Richard

Feynman ancora non riesce a decifrare benissimo cosa potesse significare quel

“qualunque cosa”; oggi, invece, sappiamo che le nanotecnologie possono trovare

applicazione nei settori più disparati: dalla medicina alla manipolazione e

trascrizione del DNA, dall'abbigliamento alla creazione di nuove batterie più

capienti e capaci di durare più a lungo. nanotechnologies

Un de mes amis (Albert R. Hibbs)

suggère une possibilité très intéressante pour les machines

relativement petites. Il a dit que, bien qu’il s’agissait d’une

idée extrême, il serait intéressant en chirurgie d’avaler le

chirurgien. Introduisez le chirurgien mécanique dans un vaisseau

sanguin, et il ira dans le cœur pour “regarder” autour. (Bien

sûr, l’information doit être récupérée.) Il trouve quelle

valvule est défectueuse, prend un petit couteau et la tranche.

D’autres petites machines pourrait être incorporées de façon

permanente dans le corps pour assister un organe fonctionnant

inadéquatement.

Foresight

Institute Feynman Prize for Theoretical and

Experimental Molecular Nanotechnology

Le nanotecnologie

hanno una data di nascita, sono

nate prima di tutto nella mente, nelle idee di un noto scienziato, Richard

Feynman, che nel 1959 tenne una leggendaria conferenza dal titolo “C’è un sacco

di spazio laggiù” in cui introdusse l'ipotesi che dal mondo dell'ultra-piccolo

sarebbero potuti arrivare grandi cambiamenti a livello macroscopico. Questa

idea, che sembrava molto strana e utopistica, probabilmente diventerà realtà nei

prossimi anni e decenni del secolo che stiamo vivendo.

un

futuro nanotech

nanotecnologia deriva da nanometro, ossia un milionesimo

di metro, ndr.

I nanocosi ora trasportano

la materia

feynman -

il genio in cattedra

-

di piergiorgio oddifreddi

INTERVISTA - PIERGIORGIO ODIFREDDI

Al giornalista Drosnin, ateo e

abituato alla ricerca dei fatti, invece la matematica fa nascere il

serio sospetto che esista un Dio…

Ma Feynman aveva gli strumenti per non farlo. Feynman ebbe tre mogli la prima, l'anima gemella conosciuta da giovanissimo e sposata quando ancora non si era laureato, muore di tubercolosi nel 1945. La seconda riuscirà a sopportarlo solo per pochi mesi «Cominciava a fare calcoli già da quando si svegliava; faceva calcoli mentre guidava l'auto, mentre stava seduto sul divano e perfino a letto», racconterà esausta. La terza lo accompagnerà fino alla morte avvenuta il 15 febbraio 1988 per due tumori rari: il liposarcoma e la macroglobulinemia di Waldenström. Le sue ultime parole: «Non sopporterei di morire due volte. È una cosa così noiosa». tiziana colusso - retididedalus.it - 2012 FEYNMAN SCRISSE UNA BELLISSIMA LETTERA ALLA PRIMA MOGLIE - DUE ANNI DOPO LA SUA MORTE MA VENNE RESA PUBBLICA NEL 1988 QUANDO LUI MORI'.

. Tutta la conoscenza scientifica è incerta gli scienziati sono abituati a convivere con il dubbio e l’incertezza Questo tipo di esperienze è preziosa e a mio modo di vedere anche al di là della scienza

Nell’affrontare una nuova situazione

occorre lasciare aperta la porta sull’ignoto in caso contrario potremmo non riuscire a trovare le soluzioni probability and uncertainty - facebook.com/Richard.Feynman.Curiosity .

...

La

cultura scientifica, sostiene Feynman, altro non è che l'applicazione

sistematica del dubbio. Procede per prove ed er ... La seconda lezione che ci regala Feynman è di tipo etico ... Quando si tratta di applicare una nuova conoscenza, anche se si tratta di conoscenza di tipo scientifico, l'onere della scelta tocca sempre e unicamente alla società nel suo complesso. Ciò non toglie, sostiene, Feynman che la società, quando deve scegliere, farebbe bene a dotarsi di un metodo scientifico: dubbio sistematico e ragionamento ipotetico-deduttivo ...

... terza

lezione che ci offre Feynman è di umiltà Intellettuale. Viviamo in un'epoca in

cui varie scienze si trovano all'apice dello sviluppo e, comunque, in un'epoca

che vanta più

scienziati di ogni altra epoca precedente. Di più. Viviamo in un

mondo che, dando un approccio dì tipo scientifico alla propria capacità di

innovazione tecnica, ha trasformato il mondo più di ogni altro secolo

precedente. Tuttavia non possiamo certo definire la nostra come un'epoca

scientifica. La grande maggioranza della popolazione ha scarse conoscenze di

tipo tecnico-scientifico e, soprattutto, ha una scarsa attitudine ad applicare

il metodo del dubbio sistematico e del ragionamento ipotetico-deduttivo. Per prova ed errore ... faculty.rmwc.edu uniba.it . RF was one of the most brilliant physicists of the past century; his work with quantum mechanics is practically unparalleled and resulted in his receiving the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965. Two years before that even, he gave a series of three lectures at The University of Washington in Seattle.

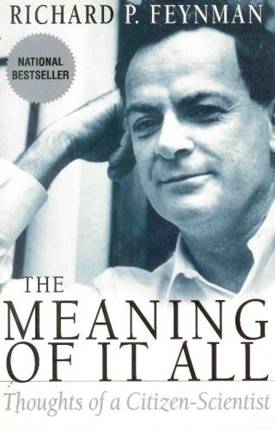

The Meaning of It

All: Thoughts of a Citizen Scientist contains those three lectures, and anyone

with even a passing interest in Feynman, or science, should grab a copy of it...

Feynman’s final

lecture is entitled This Unscientific Age –not, he says, because science was not

progressing, but because it was not the focus of the age (as the ancient Greeks

had an age of heroes, or the religious Middle Ages). He describes what he means

by a scientific age, and describes unscientific age in which he lived. In this

lecture, he jokingly undermines all of his own authority, and again discusses

religion, American politics and the ways in which science is useful in

addressing both of those arenas of thought and activity.

examiner.com - 2009

from the publisher

In these remarkable lectures--never before

published--the brilliant scientist reveals his thinking on life,

religion, politics, science--and everything in between. . 2004 - the Meaning of It All is a collection of three lectures Feynman gave in 1963. Although the words are now old--most of the ideas presented are timeless. The first lecture, entitled The Uncertainty of Science, deals with the beautifully undogmatic nature of the scientific method. Feynman discusses how we should apply this 'uncertainty principle' to more aspects of life if we are to find better ways to live and improve life. New ideas don't blossom in an environment that encourages conformity and a reliance on tradition. Good ideas aren't found from these new ideas unless some sort of scientific analysis is performed. The Uncertainty of Values probes the religious history of morality and how people can now accept the good aspects of religious values while rejecting the mythological elements of traditional religions. In fact, people can have better values by not forcing their actions into any particular religious vacuum. In this section, Feynman shows that science doesn't provide a value system, but science can provide a starting point which will be beneficial when we are faced with difficult choices to make since it can more accurately determine the situation involved. The final chapter, This Unscientific Age, covers some of the same ground explored later by Carl Sagan and Michael Shermer. Since Feynman is lecturing, rather than writing a book, his thoughts aren't nearly as concise or well-organized as the above two authors. However, the colloquial style is entertaining, easily accessible, and allows the reader to imagine that they have gone back in time to actually experience the lectures first hand. . Feynman (is) one of the century's premier intellectual optometrists: After only a few minutes, he adjusts your mental vision so that previously fuzzy concepts stand out in stunning clarity. Washington Post Book World, in a review of Six Not-So-Easy Pieces Richard P. Feynman was one of the most famous and most beloved physicists of all time. His many contributions to physics earned him the Nobel Prize; his iconoclastic outlook on life and his many curious adventures earned him the status of an American cultural icon .. 2think.org

physical

units

-

https://youtu.be/j3mhkYbznBk

the character of physical law

att.net It is useful to know how much energy corresponds to the consumption of one atomic mass unit of material: That turns out to be about 931 million electronvolts (MeV). Incidentally, the rest mass of a proton is 938 MeV, while the rest mass of an electron corresponds to 0.511 MeV. The number 938 differs from 931, because a

proton has a mass

of about 1.008 amu.

That's an unfortunate fact that we measure things in a whole series of different kinds of units

. This causes a lot of confusion . Physicists like to think that all you have to do is say ' These are the conditions, now what happens next ? ' .

was born on May 11, 1918, in Queens, New York. By age 15, he had mastered differential and integral calculus. In 1936, he attended MIT, and took every physics course offered. Later he went to Princeton for graduate studies. His interests in subatomic physics, he embarked on a lifelong quest to clarify the mathematics of a subatomic world. Feynman finished his Ph.D., and married his longtime sweetheart, ArlEne Greenbaum. She was already very ill with tuberculosis. In 1942, Feynman was asked to go to Los Alamos. Hans Bethe made the 24 year old Feynman a group leader in the theoretical division. Feynman worked on estimating how much uranium would be needed to achieve critical mass. He developed many experimental devices to test his hypothesis without blowing up Los Alamos. When Oakridge ran into safety problems while separating uranium it was Feynman who devised procedures to protect the staff from radiation poisoning. ArlEne passed away on June 16, 1945. After the war, he followed Hans Bethe to Cornell University. It was here that Feynman developed a simple notation to describe the complex behavior of subatomic particles. This notation became known as Feynman Diagrams. In the 1950s, he moved to Cal Tech. In 1965, he, along with Julian Schwinger and Shinichiro Tomonaga, shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for work in quantum electrodynamics. Feynman's popular lecture series was published in "The Feynman Lectures". The personal side of Feynman was captured in Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! and What Do You Care What Other People Think? Feynman is also known for his work on the Space Shuttle Challenger accident investigation. He shocked the world by demonstrating the failure of the O-rings. Feynman died February 15, 1988 at the age of 69, from several rare forms of cancer. atomicarchive.com

His inquiring character was first formed by his father,

who taught him that knowing the names of things wasn't the same as knowing them.

The resulting independence of mind is then firmly ratified by his first wife,

Arlene, the most wonderful person in this wonderful book. She and Feynman fall

in love while in high school and agree to marry. But while they are engaged,

Arlene is diagnosed with a fatal disease that they both know will kill her

within five or six years. Feynman marries her anyway, against the wishes of both

families, and loves her passionately till the end. She clearly deserves his

devotion. It was Arlene, in the hospital in Albuquerque, who sends her husband

pencils engraved, "RICHARD DARLING, I LOVE YOU! PUTSY." Feynman confesses to

being embarrassed to use them at Los Alamos. You see, there are all these famous

scientists and. . . . Incredulous, Arlene says, "Aren't

you proud of the fact that I love you?" And then,

without a pause, adds the words that Richard Feynman came to live by, long after

Arlene was dead: "WHAT DO YOU CARE WHAT OTHER

PEOPLE THINK?"

Richard

P. Feynman

nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1965/feynman/lecture .

When Feynman died in 1988, he left

these phrases on his office blackboard: “What

I cannot create, I do not understand"

and "know how to solve every

problem that has been solved."

This was in essence his motto. Feynman believed that to truly

understand something, you have to break it down to its simplest

parts and piece it back together.

Richard Phillips Feynman Manatthan New York 11 maggio 1918 – Los Angeles 15 febbraio 1988 Physicist, Nobel Laureate Caltech Professor of Physics, 1951-1988; Nobel Laureate in Physics, 1965. Physicist Richard Feynman won his scientific renown through the development of quantum electrodynamics, or QED, a theory describing the interaction of particles and atoms in radiation fields. As part of this work he invented what came to be known as "Feynman Diagrams visual representations of space-time particle interactions. For this work he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics, together with J. Schwinger and S. I. Tomonaga, in 1965. Later in his life he became a prominent public figure through his association with the investigation of the space shuttle Challenger explosion and the publication of two best-selling books of personal recollections. Richard Feynman served as Richard Chace Tolman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech from 1951 until his death. Papers, 1933-1988. Feynman's correspondence, course and lecture notes, talks, speeches, publications, manuscripts, working notes and calculations and commentary on the work of others are all included in this extensive collection. search.caltech.edu

L’esistenza di Feynman spesso travagliata a livello personale, ha incrociato anche grandi fatti della storia. Da giovane prese parte al Progetto Manhattan, con cui gli Stati Uniti costruirono la bomba atomica, e fu l’unico ad assistere in un’area desertica del New Mexico al Trinity Test, la prima esplosione nucleare della storia, senza gli occhiali protettivi in dotazione ai presenti. L’altra tragedia che lo vide protagonista fu l’esplosione dello shuttle Challenger nel 1986, due anni prima della sua morte. Feynman fu l’unico scienziato della commissione di inchiesta e diventò un eroe quando scoprì che il Challenger era esploso a causa di un guasto in una guarnizione di uno dei due razzi a propellente solido.

Niente male per uno che

amava suonare il bongo.

* Feynman had two rare forms of cancer, liposarcoma and Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, dying shortly after a final attempt at surgery for the former on February 15, 1988, aged 69. His last recorded words are noted as I'd hate to die twice. It's so boring. *

NUCLEARE - FBI & FEYNMAN

Che t'importa di cosa dice la gente? serena cappelli - linkiesta.it - 2012

TECNICA FEYNMAN -

METODO DI APPRENDIMENTO . . REGOLE PRIMA DI UN ESAME - INTeRIORIZZARE UN CONCETTO 1 - Pensate di insegnarlo a un bambino

Dopo aver

studiato un argomento, armatevi di block notes e provate a

ripeterlo e scriverlo o illustrarlo allo stesso tempo, come se

vi trovaste alla lavagna davanti a una classe di terza

elementare. Ripetete il concetto usando parole possibilmente

semplici, comprensibili a un bambino di 8 anni. Salteranno

subito all'occhio i punti ancora oscuri, che richiedono un

ulteriore sforzo di preparazione.

A questo punto

tornate sui passaggi che non avete capito e approfondite, fatevi

domande, trovate spiegazioni: fatelo finché non riuscirete a

tornare al punto 1 illustrando con semplicità, rigore e

chiarezza ogni passaggio. Ora che avete una spiegazione articolata di ogni punto, tornate sull'intero discorso per rendere scorrevoli i passaggi che risultano più difficili da digerire: usate la visione di insieme che avete acquisito per limare la spiegazione e renderla comprensibile, interessante e scorrevole.

elisabetta intini - focus.it - 2018

|